Is Bangsamoro on the Way to be a Sustainable Autonomous Region?

- Details

- Blog Content

- Hits: 4325

|

Political sustainability is dependent on fiscal sustainability. This means that sustaining political decentralization is not possible without fiscal decentralization. In the case of the Bangsamoro, the additional challenge is making peace and development happen in an area marred by long-standing conflicts between Muslim rebel groups and government forces.[1]

Peace is dependent on a stable political arrangement, which has to be accompanied by a sound and sustainable fiscal arrangement. This arrangement must be anchored, among others, on the Bangsamoro administration having sufficient financial resources and independent of the dole-outs of national government agencies.

According to the proposed Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL), the Bangsamoro will be an autonomous region with far reaching rights as well as responsibilities in accordance with Article X of the 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines. It will be a local government and an autonomous region in Muslim Mindanao, and as such, is an integral part of the Republic of the Philippines.

In this context, the BBL referring to the “asymmetric relationship” between the central government and Bangsamoro (Art. VI, Sec. 1), is somehow confusing. The relationship between a higher and lower level of government of one nation is always asymmetric, since the higher level will always have powers which pertain to the whole nation as also outlined in Article V of the BBL. Mostly these powers are external affairs, defense, coinage, citizenship, and immigration. The asymmetry is only with governments at the same level and thus with regard to the other LGUs and to the other regions, i.e. the deconcentrated[2] units of the national government[3].

Section 6 of Article VI of the BBL refers to devolution in line with the principle of subsidiarity[4] in both the Bangsamoro and the Philippines. It is a reiteration of the meaning of Art. X of the Philippine Constitution. It means autonomy for the Bangsamoro (Region) and the local government units (LGUs) and even reinforces the position of the LGUs in Bangsamoro since their privileges are not to be diminished for the time being (Sec. 7). For the first time the principle of subsidiarity is included in the legislation, calling for a more flexible handling of public service delivery than the Local Government Code (LGC) which assigns this directly to a LGU level.

Since Bangsamoro is a local government of the Philippines, the arguments used when talking about decentralization be it political or fiscal are valid when assessing the autonomy and self-governing potential of Bangsamoro.

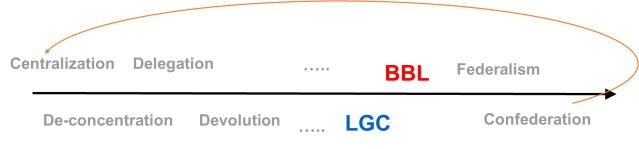

Figure 1: The Decentralization Continuum

The continuum shows the approximate position of the decentralization as granted by the draft BBL. It goes, as does the LGC, a bit further than simple devolution but the provisions are not quite as far reaching as in a federal setting. It is for sure not going as far as a confederation, for example the confederation of states during the civil war in the United States (US).

Part 1: Has Bangsamoro been provided with the necessary ingredients to Fiscal Autonomy and thus Political Autonomy?[5]

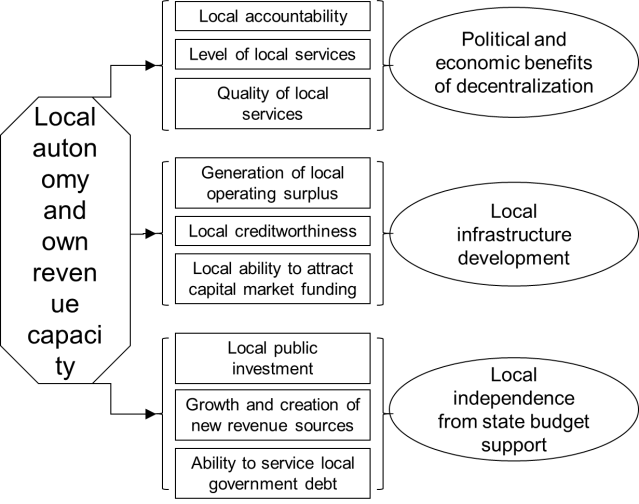

Fiscal Autonomy is a precondition for self-government or self-determination which is the goal of Bangsamoro (Art. IV, Sec. 1). An LGU without the power to raise its own revenue is unlikely to succeed. Local autonomy without command over its own resources is bound to fail.

Three points are essential to be kept in mind when talking about own revenue: It

■ strengthens the accountability of local politicians and bureaucrats

■ has the potential to improve the quality of local service delivery

■ adds a degree of freedom for development, providing funds to increase creditworthiness or for direct investments.

Figure 2: Benefits of Own Revenue & Local Autonomy

Equally important is the need to keep transaction costs at a minimum. The benefits of decentralization are not only assessed by the value of additional and/or better tailored service delivery but also the transaction cost. These consist of:

■ political (decision making cost)

■ administrative (cost of bureaucracy and coordination)

■ economic (excess[6] burden on taxpayers)

The political cost of Bangsamoro is hard to estimate, but should definitely be less than the cost brought about by the ongoing conflict in Mindanao. Thus the political transaction costs are negative and can be also subsumed under the term “peace dividend”.

The administrative cost (budget) and the economic cost (taxation) of Bangsamoro will be discussed later. The following section deals with general criteria of Fiscal Autonomy.

Fiscal Autonomy – what is needed?

Fiscal autonomy is a necessary precondition to successful and sustainable decentralization as well as the entry point to self-governance and self-determination. Four aspects need to be considered:

■ Tax policy – Which level controls tax base and rate?

■ Tax administration – Which level administers the taxes?

■ Tax assignment – Which level gets proceeds of taxes related to location?

■ Tax sharing – Which level gets what proceeds from national taxes (IRA vs. block grant)?

In the Philippines, it is the national government that controls the tax rate and base. Although there is some flexibility with regard to the rates when it comes to real property tax, the national government determines the rules. Other taxes which can be levied are cumbersome to introduce due to red tape (limits to rate increase, appeals, public hearings, threat of actions against the LCE).

The Bangsamoro has now been given the right to levy several low-yielding (more on this later) taxes, in particular, capital gains, documentary stamp, estate and donor’s tax and income tax on banks and financial institutions. “Levy” taxes does not mean that the rates and the base are to be determined by the Bangsamoro, so this important aspect of fiscal autonomy is not fulfilled (Art. XII Sec. 9). The Basque country in Spain stands out as an example of a decentralized – yet not federal – system wherein autonomy gets a boost from its complete freedom in taxation except for national VAT. Examples from federal systems are numerous. Prominent examples are the income tax rate setting by the counties in Switzerland or the state income tax in the US.

Taxes in the Philippines are up to now centrally administered, with the exception of RPT and other small taxes which can be collected by the LGUs. The Bangsamoro shall set up its own tax administration for the collection of taxes in its territory. This means that for Bangsamoro, tax administration will be decentralized (Art. XII Sec. 11). It points into the direction of autonomy and will surely improve the situation from the status quo where the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) territory is split into three Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) districts.

One important aspect that must also be considered is whether there would be enough capacity within the Bangsamoro to effectively operate a tax office. The lack of capacity and competence can jeopardize the way to autonomy and lead the Bangsamoro back to dependency or bad governance.

Assigning tax proceeds to locations – or a different way of sharing – is often a hotly debated and highly political question. Resource taxes and corporate taxes for business operations with one headquarters and several branches all over a country is an issue which needs to be resolved. Both issues are tackled in the BBL (Art. XII Sec. 32 and Sec. 11, respectively). Whether the solution to the resources should be as proposed a percentage sharing exercise or a direct assignment of royalty and taxes to different levels of government will not be discussed here. The situs of taxation issue is at least acknowledged. However, the proposed negotiation solution is less than satisfactory[7].

Resource taxes as well as other national taxes will be shared between the national government level and the LGUs using formulas. This is a tax sharing agreement as demanded by Art. X Sec. 6 (internal revenue allotment) and Sec 7 (national wealth share) of the 1987 Constitution. Whereas the Block Grant, which uses the same base as the IRA is a grant, and by design, is also a tax sharing instrument. Block grants can be determined on the basis of a multitude of criteria but they always should address vertical (or horizontal) imbalances and should generate appropriate resources for providing basic local public services, incentives for effective service delivery (i.e. not be excessive), and must contribute to securing fiscal discipline in the consolidated government system (macroeconomic stability).

It remains to be seen if the Block Grant will provide sufficient resources for the delivery of basic services on education, health, housing, livelihood opportunities, water resources development, and disaster preparedness, among other things.

In summary some of the necessary preconditions are fulfilled, while others, particularly, tax base and rate issues, are not. Whether the Block Grant is sufficient to operate a regional government will be determined below.

Fiscal Autonomy – the Other Side of the Coin

Very often, the analysis of fiscal autonomy stops at the income side. Yet the expenditure side is equally if not more important. That the income side is less important than the expenditure side is a view which was taken by the founders of the Federal Republic of Germany and also Austria. Fiscal autonomy has to be built on mutual trust among all levels of government. In Germany and Austria, the rights to set tax rates and base and to create new sources is rather limited for the lower tiers but the tax administration is mostly done by the federal states on behalf of all levels. This is a completely different setting when compared to the Philippines which is rather partnership than top-down.

Nobody talks in Germany about the dependency of the center on the states. Whereas, it is frequently heard in the Philippines that the LGUs are dependent on the center just because BIR collects the taxes on behalf of the LGUs. Those who do have forgotten about the constitutional entitlement (Art. X Sec. 6 and 7) that IRA is neither a grant nor a transfer of funds. Instead of beating a dead horse, it is time to tackle the important issues of functional assignment and the costing of services. We shall come to that below in a bit more detail.

One logical step forward after “trusting each other” is to grant the freedom of allocation of expenditure according to the priorities set by the citizens through the elected officials. Autonomy of LGUs including Bangsamoro is achieved only then when the subnational government can freely decide on how to spend its money, within a framework set by the commonly accepted rules of good governance. Accountability, transparency, and participation as well as predictability should be the paramount guiding principles in consonance with the priorities and needs of the local government. The limits as imposed by the national government on the budget allocations of LGUs in the Philippines are short of a slap in the face of local autonomy. A maximum of 50 percent for personnel services, a maximum of 20 percent for development fund, 5 percent for disaster fund, etc. spell a disaster for autonomy.

Decentralization, local autonomy, self-determination will not be achieved through these rules; these rules and limitations, in fact, are choking autonomy. It is like giving pocket money to a child so he learns how to deal with money responsibly, teaching him to be careful with spending, but telling his as well to spend 20 percent on transport, 30 percent on school lunch, 40 percent on uniform, 10 percent on school affairs, while the rest is up to him. Decentralization in a top-down setting needs the firm commitment of the center to let go and to interfere as little as possible. It is a matter of trust.

The Bangsamoro has the chance according to the draft BBL (Art. VII Sec. 26) to determine the allocation of its fiscal resources, but and this is a big BUT, only when it has passed its own budget law. Until such time the budgeting process as a whole is governed by existing laws, rules and regulations as set by the national government for all LGUs. Needless to say, the Bangsamoro budget law should be of utmost priority as so many other laws will have to be[8].

A quick note on Art. VII Sec. 27 of the BBL: it looks like the most promising and most fundamental improvement of the BBL that is not yet fully understood. It is parliamentary democracy. In a parliamentary setting, there is no need for the provision of a reenacted budget as this would lead to the same flawed setting as in the presidential system. The president or the local chief executive (LCE) can govern without the support of the elected representatives. This is a “dictatorship-like” form of government, a system failure which is avoided by a parliamentary system. As soon as the government no longer has the support of the majority of the parliament, a new government and chief minister in Bangsamoro will have to be elected. When is this mostly the case? At budget time.

The budget law has to be passed by the parliament -- no budget, no majority, no government. Passing the appropriations law for the ensuing fiscal year is the way to go, not reenactment that could only lead to muddling through to the bitter end, leaving no room to move and work for development as in the case of many LGUs. Imagine a mayor or governor ruling without support of the Sanggunian giving him no chance for a new beginning until the next election and maybe even beyond that.

Bangsamoro is designed as a regional local government unit of the Republic of the Philippines and will be, according to the draft BBL, given “more autonomy” than other LGUs. Several provisions such as the situs of taxation, the slightly larger revenues as compared to ARMM and the self-budgeting after the Bangsamoro Parliament has passed the law, point in the right direction. Still, full local autonomy and self-determination is a long way ahead. At this point, it is important to stress again that mutual trust is the essential ingredient.

Part 2: Will Bangsamoro be given a fair chance to be fiscally independent and sustainable?

This part will try to shed some light on the fiscal arrangements made for the Bangsamoro under the draft BBL. Apart from establishing what and how many funds will be available to the Bangsamoro government in its first year(s) of operation, a glimpse of the potential revenue and expenditure needs will be provided.

The base year will be the year 2013, due to statistical limitations[9]. For 2013, official statistics are available. The calculations of expenditure needs and revenue potentials do not attempt to be 100 percent correct. However, the margin of error will be small enough that the directions will be clear; shortfalls or excesses will remain as such even if accuracy is improved. And one should always remember, “The perfect is the enemy of good”.[10]

The fairy tale of the 75 billion

Very high figures for the funds allocated for Bangsamoro have been frequently quoted by politicians and the press. A figure of 70 to 75 billion Philippine pesos (PHP) is among the most quoted figures. This figure is partially based on 2015 prices and other years in some cases. A closer examination of the PHP 70 billion figure reveals a rather surprising truth.

Table 1: Funding Projections of Bangsamoro 2015 (Amounts in billions of Pesos)[11]

|

Item |

Amount |

Remark |

|

Annual Block Grant |

25.2 |

Art. XII Sec. 15 & 16 |

|

IRA of component LGUs |

19.9 |

LGU share in national taxes Not part of the Bangsamoro budget |

|

National government agency (NGA) subsidy |

12.6 |

Art. XII Sec. 21 BBL BUT no amount mentioned Not part of the Bangsamoro budget |

|

Special Development Fund |

7.0 |

One-time payment Art. XIV Sec. 2, allocated by the NG in the GAA Not part of the Bangsamoro budget |

|

Transition Fund |

1.0 |

Art. XVI Sec. 13 BBL one-time |

|

Infrastructure Fund |

- |

Art. XIV Sec. 2, 2 billion after the first year for 4 years |

|

100% National Internal Revenue Tax Collection in ARMM / Bangsamoro |

1.7 |

Art. XII Sec. 10 BBL. This is the figure for 2012[12] |

|

Normalization Fund |

2.6 |

One-time payment |

|

Total |

70.0 |

|

|

Total for allocation by Bangsamoro Government |

26.9 |

For Year 1 |

|

Total estimated allocation to Bangsamoro Government |

26.9 |

For Year 2 to 6 |

|

ARMM Budget |

24.3 |

GAA 2015 |

There it is – the 70 billion which is given to the Bangsamoro. And maybe there is more somewhere in the GAA. But what does it mean? Remember what was just said about autonomy and fiscal autonomy, in particular. This bloated figure of 70 billion has really nothing to do with funds which can be allocated to the Bangsamoro in a fiscal autonomous setting.

It is a slap in the face of an autonomous LGU within the Bangsamoro if its regular fund is to be counted as fund of the Bangsamoro region. The internal revenue allotment (IRA) is a constitutional entitlement of provinces, cities, municipalities and barangays. The LGUs, as defined in Art. X Sec. 1 of the Constitution, will then determine, within their “limited” budgetary freedom, how to allocate it. If this is in line with the goals of Bangsamoro or the national government, or of both, or only their own, is their prerogative. Clearly this cannot be counted as Bangsamoro funds.

The NGA subsidy will be allocated under the budget of the line agency in the GAA and not in the Bangsamoro budget act. The Bangsamoro government has, at most, the chance to propose or plead for the funds. Where the figure of PHP 12.6 billion comes from is not quite clear. It could be budgetary allocations for infrastructure and other projects in the GAA 2015. The amount termed as subsidy to Bangsamoro has been appropriated for projects in the Bangsamoro area and is not an addition; it will be there for the region with or without the Bangsamoro. It is also not among the funds to be allocated by the Bangsamoro parliament. Thus this amount cannot be counted as Bangsamoro funds either.

The next item on the list is the one-time PHP 7 billion allocation for rehabilitation and development (Art. XIV of the draft BBL). Again, an allocation will be made in the GAA for the first year after the Bangsamoro has been established. It is quite clear that it should not be counted as Bangsamoro funds due to the allocation in the GAA nor counted in 2015 because it is to be allocated the first year following the ratification of the BBL[13]. Thereafter it will be PHP 2 billion for 5 years – a total of 10 billion and not as often falsely assumed 10 billion every year (Art. XIV, Sec. 2). But irrespective of how much it might be, it is not to be counted as Bangsamoro fund either[14][15].

It seems quite a few of this so called Bangsamoro funds follow the same pattern as the funds provided for under the Bottom up Budgeting (BUB) program of the Aquino Administration. By nature, BUB funds are national and are controlled at the national level although they are made to appear local. If this administration would be seriously upholding the Constitution and follow the Local Government Code, all of these funds would be provided to the LGUs; the latter being able to decide where and for what purpose these funds would be used for. LGUs would not be limited to a choice from a project menu, from a pre-selection made by the center (national level) as this is an imposition on them. Again, the basic and most important ingredient in decentralization is TRUST. BUB is anti-trust, it is recentralization[16].

The transition fund is provided for the transition period and to the Bangsamoro Transition Authority to run its affairs. It is supposed to pay for PS and MOOE until the Bangsamoro has been established. This amount will not form part of a regular budget and will not be available when the Bangsamoro government will prepare its budget.

The tax collections will stay as Bangsamoro funds and are to be considered as well as the block grant. This grant is calculated as a 4 percent of the national government share[17] of the internal tax revenue collection of the third year previous to the fiscal year in question[18].

The normalization fund is a one-time payment and nothing is mentioned in the draft BBL about it. It looks like that this amount would also not be available for budgeting by the autonomous Bangsamoro. It might be just available to pay severance pay for the employees laid off in ARMM.

Applying widely accepted and followed fiscal autonomy criteria, a meager PHP 26.9 billion out of an alleged PHP 70 billion, would be available for the Bangsamoro.

Out of an alleged PHP 70 billion, a meager PHP 26.9 billion would be available applying If we now deduct from this amount the budget allocation for ARMM in the GAA which amounts to about PHP 24.3 billion, the figure becomes even smaller, almost negligible. The ARMM budget will no longer be allocated by the national government in its GAA since the ARMM will cease to exist upon the signing of the BBL. Out of PHP 70 billion, PHP 2.5 billion remains and would have to be shouldered by the taxpayers outside Bangsamoro or roughly PHP 26 per person per annum.

To make it very clear, the block grant combined with the share in national taxes collected in Bangsamoro and the proceeds from natural resources and the other minor taxes (Art. XII Sec. 9) are the revenues dedicated for Bangsamoro. Along with the freedom to budget, after a respective law has been passed, it is a big step forward towards autonomy and self-determination, notwithstanding the fact that the cost for the national government would be minimal[19]. Whether the funds will be sufficient to sustain Bangsamoro and provide enough headroom for progress has yet to be established.

Process matters

A quick glance at the process of the negotiations between Government of the Philippines and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) is quite enlightening. Although the subjects which have been placed in the Annexes[20] of the Bangsamoro Framework Agreement were negotiated in parallel, the progress, however, as measured by the signing of the different annexes, was quite different.

On the subject of fiscal autonomy, the Annexes on Revenue Generation and Wealth Sharing and Power Sharing are of importance. The first annex will determine the income or the sources of funding and the other annexes the items where the funds will be spent on, since they are in the sole responsibility of the Bangsamoro. The first was signed in July 2013 and the others in December 2013.

As it is so often the case, it seems the annexes were negotiated without really taking into consideration what was negotiated in the other panel. Or to put it in fiscal terms, the expenditure side was determined without taking the income available into consideration. Time is always a crucial factor but not giving enough time to consider the most important fiscal factors will haunt both sides – GPH and MILF – for a long time or result in a complete failure.

The right process is to, first, be clear about what should be done by what level of government, i.e. by the national government, the Bangsamoro, and the LGUs. The next step is to cost the delivery of the allocated services and goods by the different levels, taking the principle of subsidiarity as guiding principle. The revenues have to be assigned to the different levels AFTER the costing, not BEFORE. This is, in most cases, the recipe for failure. The powers should have long been assigned before the revenues were negotiated.

The right approach would have been to first agree on certain principles and define the limits to decentralization. This would have included the agreement on the principle of esteem and the principle of subsidiarity. Further, the powers of the national government have to be clear. In the case of Bangsamoro, the LGC and the powers vested in the LGUs further limited the range that was open for “negotiation”. If a Bangsamoro LGC will be drafted and passed into law, it would be highly advisable to undergo an exercise called Functional Assignment. It will clearly outline which functions – delivery of goods and services, policy setting – will be taken up by each of the levels of local government including the Bangsamoro. To establish the expenditure, a costing exercise is required. By comparing the would-be determined cost with the available revenues, the results will indicate the possibilities of each government and their needed policy actions. This process will ensure avoidance of “unfunded mandates”, the claim of too little or too high allocations, and will put a solid base to negotiations and renegotiations between the levels of government. In case that there is a window of opportunity to renegotiate BBL, or in the case of the drafting of the Bangsamoro LGC, a functional assignment approach[21] should be chosen.

The just outlined process was reversed in the BBL context so that fund allocation was undertaken first without knowing whether it will be enough or too much. In the following a quick and simple method to estimate the needed funds, i.e. the budgetary requirements of Bangsamoro, will be established before this is put against the revenues of the Bangsamoro.

What are the budget requirements of Bangsamoro to sustain the government operation?

A per capita approach[22] based on the 2013 GAA is used to establish the budget requirements of Bangsamoro. The results are based on official government statistics for the year 2013 and on the population census of 2010. To arrive at 2013 population figures, the 2010 figures were extrapolated using the average annual growth rate for the Philippines of 1.9% [23]. The population of Bangsamoro includes that of all plebiscite areas including Cotabato City and Isabela City, the 6 municipalities in Lanao del Norte as well as the 39 barangays in North Cotabato.

Table 2: Population in million

|

Population |

2010 |

2013 |

2013 |

|

Under 20 |

|||

|

Philippines |

92.3 |

98 |

43 |

|

Bangsamoro |

3.8 |

4.1 |

1.64 |

|

ARMM |

3.25 |

3.45 |

1.38 |

|

Phil excl. ARMM |

89.05 |

94.55 |

41.62 |

|

Source: Philippine Statistics Authority[24] and own calculations |

|||

The under 20 population has been established using the cohort population of 2010 for those 0 to 19 years old and by applying the same fractions for the total population to the ARMM and Bangsamoro population.

Assuming that every citizen has the right to the same services and deliveries by government, a population-based estimation of the budget requirement was undertaken using Art. V, Sec. 2 and 3, Art. XVI, Sec. 7 and Art. IX, Sec.8 (Basic Services) as guideline for the budgeting and the budgeting units of the Bangsamoro government. The base for the funds and thus the level of service quantity and quality are the per capita funds provided in the Philippines, based on the GAA of 2013 (POP). In case the budgeting unit was already a department in ARMM and had a budget, the Philippine population excluding ARMM served as base (POPex).

The budget allocations do not include infrastructure investment and programs and projects as they are still being funded by the national government according to their national priorities. The base figures consist in almost all cases of PS and MOOE only; no CO is included. Certain allocations in the GAA 2013 for ARMM have been moved to Bangsamoro as well as the SUCs ARMM allocation under the Department of Education (DepEd).[25] However, SUCs in Cotabato City and other potential Bangsamoro areas have not been considered.

Table 3: Estimates of Bangsamoro Budget Requirements (in million pesos)

|

Budgeting Unit / Item |

NG Allocation based on GAA 2013 |

Bangsamoro |

Method / Remark |

||

|

% |

|||||

|

GOCC Subsidies |

NIA |

1722 |

72.04 |

0.28 |

POP |

|

PCA (Coconut) |

109.50 |

0.43 |

Allocation ARMM |

||

|

PH Crop Insurance |

1184 |

49.53 |

0.20 |

POP |

|

|

National Elec. Adm. incl. Rural Elec. |

141.60 |

0.56 |

Allocation ARMM |

||

|

National Housing |

21737 |

942.59 |

3.72 |

POPex |

|

|

OP / Chief Minister |

2400 |

104.08 |

0.41 |

POPex |

|

|

Congress / Parliament |

3239 |

140.44 |

0.55 |

POPex |

|

|

COA |

7645 |

319.84 |

1.26 |

POP |

|

|

CSC |

876 |

36.65 |

0.14 |

POP |

|

|

DSWD |

54862 |

2379.00 |

9.39 |

POPex |

|

|

DBM |

928 |

38.82 |

0.15 |

POP |

|

|

DAR |

19122 |

829.19 |

3.27 |

POPex |

|

|

DA |

1627.54 |

6.43 |

|||

|

DA all units |

17216 |

746.54 |

2.95 |

POPex |

|

|

F2M Road ARMM |

503.00 |

1.99 |

Allocation ARMM |

||

|

Other Projects in ARMM |

378.00 |

1.49 |

Allocation ARMM |

||

|

DENR |

16029 |

695.07 |

2.74 |

||

|

DepEd |

12389.73 |

48.92 |

|||

|

DepEd all units |

225401 |

8,881.73 |

35.07 |

Under 20 |

|

|

Madrasah |

200.00 |

0.79 |

Allocation ARMM |

||

|

Computer |

50.00 |

0.20 |

Allocation ARMM |

||

|

Kindergarten |

52.00 |

0.21 |

Allocation ARMM |

||

|

Science and Math |

27.00 |

0.11 |

Allocation ARMM |

||

|

SUCs ARMM |

3,179.00 |

12.55 |

Allocation ARMM |

||

|

DILG |

815.84 |

3.22 |

|||

|

Off Sec |

3621 |

157.02 |

0.62 |

POPex |

|

|

Bureau of Fire Pro |

7894 |

330.26 |

1.30 |

POP |

|

|

Bureau of Jail Mgt. |

5774 |

241.57 |

0.95 |

POP |

|

|

Rural Water ARMM |

87.00 |

0.34 |

Allocation ARMM |

||

|

DOF |

395.91 |

1.56 |

|||

|

Off Sec |

618 |

25.86 |

0.10 |

POP |

|

|

BIR |

7543 |

315.57 |

1.25 |

POP |

|

|

BLGF |

195 |

8.16 |

0.03 |

POP |

|

|

Treasury |

527 |

22.05 |

0.09 |

POP |

|

|

SEC |

236 |

9.87 |

0.04 |

POP |

|

|

COOP |

332 |

14.40 |

0.06 |

POPex |

|

|

DOLE |

250.90 |

0.99 |

|||

|

Off Sec |

2815 |

122.07 |

0.48 |

POPex |

|

|

TESDA |

2971 |

128.83 |

0.51 |

POPex |

|

|

DOST |

265.82 |

1.05 |

|||

|

Off Sec |

2343 |

101.60 |

0.40 |

POPex |

|

|

Other Units (50%) |

3787 |

164.22 |

0.65 |

POPex |

|

|

DOT |

2783 |

120.68 |

0.48 |

POPex |

|

|

DOTC |

3330 |

144.40 |

0.57 |

POPex |

|

|

DPWH |

11179 |

484.76 |

1.91 |

POPex |

|

|

DTI |

3544 |

153.68 |

0.61 |

POPex |

|

|

NEDA |

860 |

35.98 |

0.14 |

POP |

|

|

DOH |

49900 |

2,163.83 |

8.54 |

POPex |

|

|

Judiciary, Art. X |

14800 |

619.18 |

POP |

||

|

|

|||||

|

Total Requirement |

25326.61 |

||||

Source: Own calculations

Based on the 2013 figures, the total estimated budget required is slightly more than PHP 25.3 billion, almost double the ARMM budget of PHP 13.2 billion in the GAA 2013. Still, this is a conservative estimate since certain items and line departments have not been included. These are energy, civil registrar, Islamic affairs, Indigenous People, higher education, etc. They were excluded since fully fletched offices might not be necessary for some of them and they should be integrated in the Chief Minister’s office as in the case of intergovernmental negotiation teams in the line ministries or the Bangsamoro Parliament. The budget requirements are also on the conservative side since economies of scale which occur with larger units – like the national government – cannot be expected in Bangsamoro, and therefore the unit cost would be higher.

Almost half of this PHP 25 billion will have to be allocated to education. Quality education is one of the declared major objectives in the Bangsamoro. However, whether this amount, which mostly caters for the salary of teachers and other personnel, is enough to ensure an increase of e.g. the simple literacy rate from 81% to the national average of 96%[26] is another question. To avoid the risk of endangering higher education, 12% of the budget need to be allocated to SUCs. Close to 10% of the budget is required by both social welfare as well as health. The 6.5% needed for agriculture and fisheries include 3.5% of funds for investment in the current ARMM appropriated in the GAA. Also a minor portion of the DILG and the GOCC subsidies consist of CO for ARMM. These items were included in the budget estimate since the provisions of the BBL in Art. XII, Sec. 21 and Art. XIV Sec. 2 are not clear if it will be covered by the national government after Bangsamoro has been established or not.

The Bangsamoro justice system (Art. X) is a three-pronged system consisting of the Shari’ah law system, the traditional or tribal justice system, and an alternative dispute resolution system. The necessary funding is difficult to estimate. With its 2.5% share, it is a budget item which is higher than that for a Bangsamoro DPWH and almost as high as the estimated Bangsamoro DAR and Bangsamoro DILG share. Both of which exceed 3%.

The share of DILG would be substantially higher if the Bangsamoro Police (Art. XI) would not be part of the Philippine National Police and would not be catered for by the allocations in the GAA of the national government (Art. XI, Sec. 2). The cost of the Bangsamoro police is in the magnitude of PHP 2 billion assuming that a Bangsamoro police person costs on average as much as a member of the PNP. These costs are approximately PHP 480,000 per officer per year using the GAA 2013 allocation for a 140,000 strong PNP force. According to Art. XI Sec. 9, at least 1 police officer per 1,000 inhabitants in Bangsamoro is envisaged. This would mean a force of at least 4,100 police officers.

On the other hand, certain powers given to the Bangsamoro government have already been given to the LGUs in the LGC. These include the regulation of small-scale mining and waste management. No funds were thus allocated to those except for the portions of the Bangsamoro DENR and DOST budgets which could cater for geological and environmental services.

Again it should be emphasized that almost all investment funds are not appropriated in the Bangsamoro budget but in the budget of the National Government as outlined in the BBL. Recalling the remarks made regarding fiscal autonomy and its need to make self-determination a reality, one has to be concerned for the development process of the Bangsamoro.

The Bangsamoro parliament and government will have no budgeting power and most likely no control over the implementation of major investments in the Bangsamoro. As it looks like, the Bangsamoro government will be merely allowed to send a wish list, which is called a development plan, to the Congress of the Philippines and hope it will be honored one-on-one, and that their priority projects will be given the same or higher priority than those of any other region. Further, they can only hope that the Bangsamoro projects will be part of the line agency’s menu in Manila. The following might be an exaggeration but proves the point: If Bangsamoro aspires a public market for municipality X, they should not be told that public markets are no longer financed by the national government and Bangsamoro could instead get an airstrip, but on another island. This lack of control over an essential part of the development is the most serious concern for the fiscal and thus political economy, apart from the fact that the funding for the budget requirements might be insufficient.

How much does Bangsamoro really get?

In a previous section we have established that the PHP 70 billion for Bangsamoro is nothing but a smokescreen. Large amounts are due to the LGUs – provinces, cities, municipalities and barangays. These are already and would under any circumstances be appropriated for the Bangsamoro area as national subsidy or as one-time allocations for dearly needed infrastructure as in Art XIV, Special Development Fund. The development gaps in the ARMM region and thus also in Bangsamoro are substantial. Land and sea infrastructure are way below national averages. The road density in ARMM is the lowest in the Philippines with 0.03km/sq.km compared to 0.07 in Mindanao and 0.09 in the Philippines[27]. To achieve the same road density as in Mindanao, an investment of PHP 10 billion would be required, and a whopping PHP 16 billion to get to the national average. Comparing that to PHP 17 billion rehabilitation and development fund for 6 years means that only the roads can be built, but no power generation, no transmission and distribution lines to reduce the power outages from 8 hours per month to less than 4 hours to be in line with the rest of Mindanao[28], or any other infrastructure investment.

Other indicators of development gaps of the ARMM/Bangsamoro region have been presented at several forums and seminars and have been highlighted[29]. Closing the gaps is an absolute necessity and requires a substantial effort to break the vicious cycle of underdevelopment, poverty, informality, and conflict[30].

Besides the required investment funds which have to be allocated in much larger amounts by the national government, it is still not clear how much of the budget estimates can be covered by the “income” allocated to Bangsamoro.

Table 4: Revenue of Bangsamoro (2013 figures in million Pesos)

|

Source |

Amount |

Remarks |

|

Block grant |

16519.5 |

4% of the national internal revenue tax collection |

|

Additional Taxes |

9.4 |

Documentary Stamp, Capital gains, Estate Donors Tax (Art. XII, Sec. 9 a) to d)) |

|

Taxes collected by BIR (in ARMM) |

2307.4 |

BIR Statistics[31] |

|

Revenue from natural Resources (Mining Tax) |

(8220) |

Nonmetallic proceeds are 100% for LGUs[32] National government taxes, fees and royalties in 2010[33] |

|

Total |

18836.3 |

All revenues, which can be ascertained at present without the passing and implementation of a Bangsamoro tax code, are at PHP 18.8 billion. Even when a small fraction of the Mining Tax would be added together with the amount for the Tax Remittance Advise of around 400 million[34], the shortfall would be in approximately PHP 6 billion or almost 25 percent.

A major portion of these revenues is the block grant of 4 percent of the national internal revenue taxes minus the LGU’s shares. For 2013, the total amount – for both the national government and LGUs – was PHP 688312.4 billion[35] and the share for the national government amounted to PHP 412987.5 billion. Four percent of this is the Bangsamoro share of PHP 16.5 billion.

The collection from the additional taxes allocated to Bangsamoro is a “staggering” PHP 9.4 million[36] (!). It is really ridiculous to even list it. This increase of the Bangsamoro tax base is merely window dressing. It could have been expected that taxes which will provide substantial revenue would be allocated or further tax sharing would be agreed.

The taxes collected by BIR in ARMM in 2013 amounted to PHP 2.3 billion and imply a tax-to-GRDP ratio of 2.3 percent. This is way below the Philippines tax-to-GDP ratio of 12.9 or that of the US of 10.6[37]. In fact, no country in the world listed in the World Bank statistics comes even close to that. Malaysia has 16.1 percent and the highest are Denmark with 33.3 percent and Macao with 37 percent.

Considering these ratios, major efforts have to be undertaken to raise additional revenue through improved collection or additional taxes – certainly, a mammoth task given the probable lack of capacity in Bangsamoro. A bit of relief could come from the inclusion of the tax revenues of Cotabato City and the other areas to be included in Bangsamoro. A major contribution to close the PHP 6 billion gap is yet to be expected in the short run. There is, however, potential in the long run. Should the national ratio be attained, additional PHP 10 billion could be collected, of which 75 percent or PHP 7.5 billion would accrue to Bangsamoro.

This will require special efforts, apart from industriously collecting all taxes, in the formalizing of businesses, labor force, and property market as well as the cross-border trade with Sabah. Higher revenues are to be expected from reducing the informal labor force from 80 percent to a level more in line with the 40 percent for the rest of the Philippines. Their income share of 55 percent of total income in ARMM needs also to be reduced to a level comparable with the national average of about 25 percent[38]. Business registration and the payment of taxes by the 25 percent unregistered and the 50 percent non-bookkeeping businesses will also contribute to reducing the deficit. These measures have to be part of the efforts to raise the tax collections by an estimated PHP 7.5 billion.

Cross-border trade provides income to traders and rent-seeking state agents particularly in Tawi-Tawi and Sulu. The income for the groups is estimated to be about PHP 500 million and thus a formalization and taxation could bring about PHP 100 million in additional revenue[39].

What else could help to lessen or close the expected budget deficit? A certain relief can also be expected in the transfer of taxes collected in Manila from companies with operating branches in Bangsamoro. The so-called situs of taxation matter is a long-standing issue also with the LGUs. It is hard to estimate how much additional revenue it would generate, but looking at the top 500 taxpayers as listed by BIR[40], it can be imagined that quite a number will have some branches in Bangsamoro. Still without accurate data from BIR and some further research, an estimate is currently impossible.

It is also very difficult to estimate the potential proceeds from the exploration, development and utilization of natural resources (Art. XII, Sec. 32). The revenue of the non-metallic resources is allocated to the LGUs (LGC). For metallic minerals and fossil fuels, a sharing with national government (75:25; 50:50) is envisaged. The estimate for the whole of the Philippines is PHP 8.2 billion[41]. According to the ARMM BOI, one major investment has been made in metallic mining in the past year[42]. However, according to mining intelligence information[43], no large or medium scale mining operation is ongoing in ARMM or in the Bangsamoro. Only the future will tell if there is considerable natural resource wealth in the area. Although Art. XIII Sec. 15 gives the Bangsamoro government the right to regulate small-scale mining, this seems in conflict with the powers vested in the provinces, according to the LGC. It also contradicts the provision of Art. VI Sec. 7 which states that the rights of the LGUs are not to be diminished unless altered in a Bangsamoro LGC. No or only minor contributions to Bangsamoro revenues are expected in the short or long run.

The last Item to bring some relief, at least in the medium to long run, could be a change in the internal revenue tax base. In particular, the LGUs argue that value added tax (VAT) and collections by the Bureau of Customs (BOC) should be included in the revenue base which is used to calculate the IRA and will be used to calculate the Bangsamoro block grant. If the advocates for the inclusion of VAT and BOC collections will succeed, roughly about PHP 125 billion would be added[44]. This might add PHP 5 billion. Other proposals, however, aim at a 50:50 sharing of the current base between the national government and LGU. In this case, a reduction of about the same amount would be the result for the Bangsamoro region. If both proposals will push through, which would be the most favorable situation for the LGUs[45] and would mean additional PHP 250 billion IRA, the effect for Bangsamoro would be zero since the increase would be eliminated by an equally large decrease.

What would be most likely in the short and in the long run is hard to tell. Clearly, something has to be done to increase the IRA, but not under the current administration. A possible and the least (politically) sensitive option seems to be a 50:50 sharing, which would be a disaster for Bangsamoro since the block grant would be reduced by PHP 5 billion. This case may lead to a renegotiation of the percentage. Also likely, because of a pending Supreme Court case, is the inclusion of VAT and BOC collections. This would be favorable for the Bangsamoro because this would increase its block grant by about PHP 5 billion and would bring relief to its budget problems.

More revenue could also be generated by imposing additional taxes and the Bangsamoro would be allowed to do so (Art. XI, Sec 6). But would it be prudent to do so when a relatively underdeveloped region wants to catch up with its neighbors? Most economists would recommend this as a last resort. Instead of imposing new taxes, fees and charges, the existing sources should be fully exploited. In addition, it has to be carefully examined which types of taxes would be in line with an Islamic taxation and its results for the revenues of Bangsamoro. This measure has, in the long run, the potential to also contribute to the gap filling between revenues and expenditure, however little with regard to the investment gap.

Table 5: Closing the Gap (billions of Pesos)

|

Short term (1-5 years) |

Long term (5-10 years) |

Remarks |

|

|

Estimated Budget Deficit |

6 |

6 |

|

|

Tax Collection |

1 |

7.5 |

|

|

‘Situs’ |

? |

? |

Could be significant |

|

Mining |

- |

? |

Minimal, short term |

|

Others |

.1 |

Cross border trade |

|

|

Block grant base |

5 |

5/-5/0 |

|

|

Deficit - / Surplus |

0 |

12.6/1.6/7.6 |

As it looks like, only a favorable Supreme Court decision would be able to bring some relief in the short run. The revenue increase is about equivalent with a 1.5 percentage point increase of the block grant percent allocation[i]. This, combined with a collection drive by BIR supported by the Bangsamoro government could just close the gap. In case no base increase materializes, a renegotiation of the block grant has to be initiated aiming at 5 to 5.5 percent. Even better would be the “functional assignment” approach outlined above.

The situation in the long run is completely dependent on the decision about the IRA sharing formula and the VAT BOC collection inclusion. In the best case – expanded tax base, full exploitation of the tax collection potential and some additional revenue from the other sources – the gap can be closed and a sizeable amount could be available for investments. Bangsamoro would be fiscally autonomous and would have a good chance to survive politically as well.

The worst case – no inclusion and a 50:50 sharing between NG and LGUs, but still largely realizing the taxing potential – would mean muddling through. Fiscal autonomy would be elusive and political survival a gamble – a situation close to that of a “failed experiment”.

The LGU most favorable case – inclusion and a 50:50 sharing between NG and LGUs, but still realizing the taxing potential – could still lead to a workable situation. A surplus in the magnitude of additional collection and situs taxation, coupled with some mining and other proceeds, will be available for investment. The development would be much slower than in the best case scenario.

In summary, if the Bangsamoro is not to stumble from the beginning into a budget deficit situation or reduce the services to a less than satisfactory level and fall short of the BBL provisions outlined in Art. IX (Basic Rights), it would require an additional of at least PHP 6 billion (2013). In the medium to long term, its tax collection has to also improve substantially. An indication on whether this is a realistic assumption can be derived from a crude analysis of the revenue situation of the ARMM and Bangsamoro LGUs.

Revenues and Revenue Structure of the LGUs of Bangsamoro[46]

Although the revenue of the Bangsamoro LGUs is of little concern for our analysis of the financial survival of Bangsamoro as an autonomous region, some indications, particularly for the revenue raising potential, can be obtained by looking at the revenue structure of Bangsamoro LGUs.

The LGUs of Bangsamoro received a total income of PHP 12.1 billion in 2013. Most of which was their own share in national internal revenue. The PHP 11.5 billion IRA is obviously deemed sufficient by the local authorities to provide the services and make the investment for the development of their constituents. Their own additional revenues amount not even to 4 percent. At least the cities collect 14 percent of their revenue from sources like real property tax (RPT), business tax, and fees and charges. The difference of cities within ARMM, and currently outside but are proposed to be included in the plebiscite, is not significant.

What is possible could be shown by the comparison with two cities of similar size in the Visayas. Mandaue and Dumaguete collect more than or close to 50 percent of their income on their own. Business taxes play a slightly more prominent role than RPT[47].

This tendency continues when figures for Provinces are compared. While La Union collects more than 30 percent on its own, of which 30 percent is sourced from RPT, the Province of Sulu just manages a dismal 0.3 percent in total[48]. Both provinces are of comparable size as shown by the IRA revenue of close to 700 million Pesos.

Table 6: Revenue of Bangsamoro LGUs and selected others (millions of Pesos)

|

IRA |

Other Own |

Nat Taxes |

Total |

% |

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

2/4 |

|

|

Province |

4086 |

124 |

107 |

4318 |

2.9 |

|

Cities |

1396 |

228 |

7 |

1630 |

14.0 |

|

Municipalities |

5078 |

101 |

34 |

5213 |

1.9 |

|

Barangays |

972 |

972 |

|||

|

Total |

11531 |

454 |

148 |

12132 |

3.7 |

|

Marawi |

334 |

72 |

6 |

411 |

17.4 |

|

Cotabato |

451 |

123 |

0 |

575 |

21.5 |

|

Mandaue |

443 |

801 |

8 |

1252 |

64.0 |

|

Dumaguete |

253 |

232 |

12 |

497 |

46.7 |

|

Sulu |

662 |

2.4 |

37 |

701 |

0.3 |

|

RPT |

2.0 |

2 |

0.3 |

||

|

La Union |

678 |

389 |

144 |

1211 |

32.1 |

|

RPT |

119 |

119 |

9.8 |

Source: BLGF Statement of Income and Expenditure LGUs 2013 and own calculations

The revenue collection effort of LGUs in ARMM is way below those of comparable LGUs in the rest of the country. Whereas cities only collect about 20 percent to 30 percent of other cities, provincial collections are up to 60 times higher outside Bangsamoro.

The lack of collection effort at the local level also leads to a rather pessimistic assessment on the Bangsamoro at the regional level. The collection effort of local tax authorities seems even lower than the rather lackluster effort of BIR in the ARMM region. Should the collection performance of national taxes in Bangsamoro by a Bangsamoro BIR not improve substantially and fast, regional fiscal autonomy and self-determination will be as elusive as ever.

Major Findings

■ Fiscal Autonomy and thus Political Autonomy has to be built upon trust by both the national government and the Bangsamoro government, and the Bangsamoro LGUs.

■ Fiscal Autonomy requires that revenues and expenditure are determined by the autonomous unit of government within an agreed framework. The passage of a Bangsamoro budget law is of utmost priority.

■ It is imperative that the Bangsamoro can determine the investments for development, or at least have a major influence on the decision. If these decisions are ultimately made by the center (national government), no autonomy and no self-determination can be achieved.

■ The net transfer to Bangsamoro – using minimum autonomy criteria, and considering the current spending in ARMM – is in the magnitude of PHP 2 to 5 billion. The higher figure stems from the financing of the Bangsamoro police force through the center.

■ Allocating 4 percent for the block grant is arbitrary and should be replaced by results obtained through a functional assignment analysis and based on the principle of subsidiarity including the Bangsamoro LGUs. In the meantime a per capita based approach to arrive at the transfers could be chosen.

■ A Bangsamoro government would, based on 2013 figures, need a budget of at least PHP 25 billion. Even this is a shoestring budget. The revenues, also based on 2013 figures, only amount to PHP 19 billion.

■ The financial gap of PHP 6 billion, in the short run, cannot be closed without additional transfers from the center.

■ Closing the gap might only be possible if the Supreme Court rules that VAT and BOC revenues form part of the national internal revenues as this will expand the base for the block grant calculation by about PHP 100 billion.

■ This shortfall does not include ANY allocations for development investments as the budget covers almost no capital outlay (less than PHP 1.5 billion).

■ In the long run, substantially increased tax collection effort of national taxes in Bangsamoro, leading to the tax-to-GDP ratio as for the Philippines of 12.6 percent, plus the situs taxation rule (more than PHP 7.5 billion) could close the gap.

■ This, combined with the expanded block grant base, could provide the necessary funds for development investment and would be a major step to fiscal autonomy and thus potentially to political self-determination.

■ The current tax collection performance in ARMM by BIR and that of the LGUs is extremely poor, casting substantial doubt on the viability of this proposal. Substantially improved own revenue collection as fiscal autonomy criteria is an imperative.

■ The shadow economy in Bangsamoro plays a major role and needs to be formalized swiftly, as it is a prerequisite for investor confidence and government revenue.

Recommendations

The BBL in its current form is a step in the right direction of autonomy. It takes decentralization one step further when compared to RA 6734 and RA 9054 as well as the Local Government Code (RA 7160). However, major “improvements” concern more Bangsamoro’s political setting than its fiscal autonomy. A parliamentary democratic setting, with the potential of representation by the bright and the honest rather than the rich and powerful, should not be gambled away. It could break the dominance of the ruling cliques and dynasties.

On the other hand, the Bangsamoro could only survive if the other ingredients – foremost is the fiscal arrangement, provide the needed support. At present, it rather looks like this part could become a stumbling block. In general, the center needs to let go and the Bangsamoro needs to substantially improve the governance performance. Trust in the fulfillment of rights and responsibilities (also fiscal) is necessary.

Total transaction cost of the autonomy of Bangsamoro would be low. Political cost can be compensated with the cost of the conflict. The administrative transaction cost will be very small, since the ARMM budget allocation is almost as high as the block grant and the economic cost would simply be in line with the rest of the Philippines.

Solutions for the major stumbling blocks could be in the form of:

For the development investment: Rather than providing the investment and rehabilitation funds through the GAA, controlled by the national government, these funds should be provided as special grants for broad categories such as education, health, road infrastructure, etc. The decision when, where and for what exactly these funds should be with the Bangsamoro parliament/government. The Commission on Audit (COA) should perform its duties in cooperation with the Bangsamoro branch. This would be in the direction of fiscal autonomy and not recentralization, as the current proposals do. It could also be a model for LGU funding rather than the control approach of the BUB.

For the PS and MOOE budget: A more flexible and development oriented approach should be chosen to avert the immediate collapse due to the lack of budget resources and/or insufficient service delivery for the citizens of Bangsamoro. Government has to serve its citizens and in particular those in an area marred by conflict resulting in underdevelopment. A per capita approach – since development through the budget is for people – coupled with a matching adjustment of the block grant is needed. In the medium-term, a functional assignment approach inclusive of the LGUs, bolstered by a Bangsamoro LGC and a new IRA arrangement is recommended.

For the revenue side: The only reliable source is the exhaustion of the available revenue sources, national and local. This requires a major improvement in performance. Given the exiting capacities this seems a “mission impossible”. Major and massive capacity development programs are required. Here, the aforementioned Bangsamoro political setting could be a substantive asset. It can be assumed that in a parliamentary setting, supported by a merit-based accession in Bangsamoro, a professional and not term-based civil service might be emerging.

About the author

Dr. Herwig Mayer is special policy advisor at the League of Provinces of the Philippines. He was project manager for 21 years at GIZ Deutsche Gesellschaft, providing support to the decentralization drive of the Philippine government and government reforms such as business permit and licensing system (BPLS), inter-local cooperation, and local planning. Apart from being a decentralization expert and an economist by profession, Dr. Mayer is also a consultant on public finance management and local taxation. He holds a Doctor of Philosophy in Economics from University of Regensburg, Germany. He presented this paper during the third of the seven-series Muslim Mindanao Autonomy Roundtable Discussions conducted by IAG at the Senate of the Philippines from June to September 2015.

1. ARMM Roundtable Summits on Peace and Security, GTZ German Technical Cooperation - Decentralization Program

2. Note that a de-concentrated level is not a devolved level. Regions are as de-concentrated level part of the national level of government. They don’t have own revenue and no budgeting powers.

3. As there is only one autonomous region in Muslim Mindanao. Art. X of the Constitution allows autonomous regions in Muslim Mindanao and the Cordilleras. Thus there could be 2 or 3 autonomous regions in Muslim Mindanao since Art. X does not specify the number.

4. Subsidiarity means public services should be delivered by the lowest level that can do this efficiently and effectively. It means this LGU level needs not be the same at all times and in all areas.

5. See also B. Spahn, Decentralization in the Philippines in the Light of International Experiences; in Revisiting Decentralization in the Philippines 2006, Published by German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ) Decentralization Program and Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Manila 2006

6. Excess taxes and not taxes in general!

7. The so called Massachusetts formula using pay roll, number of employees, etc. as criteria is long known and practiced elsewhere but NOT by BIR.

8. It looks like the tactic is: overwhelm them with work and they will eventually succumb.

9. http://data.worldbank.org/country/philippines The Philippine statistical system has taken a nose dive from 2009 from 92 index points to 78 in 2014.

10. http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Voltaire

11. Based on the presentation of Atty. Naguib G. Sinarimbo: Fiscal Autonomy: Context And Status In ARMM; Sofitel Hotel, Pasay City April 13, 2015

12. Republic of the Philippines Department of Finance BUREAU OF INTERNAL REVENUE Revenue Collections by Region/ Province CY 2012 (In Million Pesos), 74436 Collection Monthly (NSCB) 2012 (WEB).pdf

13. Economist would now even argue with Present Value and discount the figure.

14. See also Art. V, Sec. 2, 12. There it is clearly spelled out that infrastructure investments will be funded by national government and Bangsamoro has only the right of proposal.

15. Whether this amount is sufficient for the needed investment in infrastructure in the region is a completely other story. See also the section on budgetary requirement below.

16. It is partly the fault of the LGUs who failed to put up a strong unified force against the recentralization moves of the center. See also H. Mayer in Highlights of the Conference; in Revisiting Decentralization in the Philippines 2006, Published by German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ) Decentralization Program and Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Manila 2006

17. The national government share is 60% of the total. The remaining 40% are the IRA for the LGUs.

18. For example the base year for Fiscal Year 2012 is 2009.

19. However the people who put together the figure have omitted several smaller items and where not including all the costs. E.g. the cost for the Bangsamoro Police will easily amount to 2 billion a year.

20. They are forming the core of the different articles of the BBL.

21. Functional Assignment in Multi-Level Government Volume I: Conceptual Foundation of Functional Assignment and Volume II: GTZ-supported Application of Functional Assignment, Published by: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH, Sector Network Governance Asia www.gtz.de/en/weltweit/asien-pazifik/21084.htm , Eschborn 2009

22. This approach implies, that in case of a population increase due to a plebiscite the budget will be increased accordingly. Of course a decrease in the population would also mean a decrease in the budget. A decrease in population would therefore not be a solution to solve ‘budget problems’. The same should be true for the revenue side and for example the block grant could be linked to the population to be served.

23. The population growth rate of the ARMM was for the past 10 years substantially below that of the national average whilst it was way above the national average for the previous 10 years period. This could indicate a statistical error or a massive in and out migration to and from ARMM over time. http://web0.psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/attachments/hsd/pressrelease/Population%20and%20Annual%20Growth%20Rates%20for%20The%20Philippines%20and%20Its%20Regions%2C%20Provinces%2C%20and%20Highly%20Urbanized%20Cities%20Based%20on%201990%2C%202000%2C%20and%202010%20Censuses.pdf

24. http://web0.psa.gov.ph/content/2010-census-population-and-housing-reveals-philippine-population-9234-million

25. See Government of the Philippines: Official Gazette, 28th December 2012, General Appropriations Act FY2013; http://www.dbm.gov.ph/?page_id=5280

26. http://www.nscb.gov.ph/secstat/d_educ.asp 2008

27. Socio-economic Trends in Mindanao, Foundation for Economic Freedom, Inc., 2014 p.60

28. Socio-economic Trends in Mindanao, Foundation for Economic Freedom, Inc., 2014 P.61

29. See presentation of Atty. Naguib G. Sinarimbo: Fiscal Autonomy: Context And Status In ARMM; Sofitel Hotel, Pasay City April 13, 2015

30. See also Atty. B. Bacani, The Bangsamoro Peace Process, Presentation at the GIZ Annual Management Meeting, 23rd Feb. 2014

31. Republic of the Philippines Department of Finance BUREAU OF INTERNAL REVENUE Revenue Collections by Region/ Province CY 2013

32. RA 7160 Local Government Code.

33. https://ibonreads.wordpress.com/tag/mining/

34. How Tax Remittance Advise is to be treated in respect to the provisions in BBL is not clear the amount could varies over time (2002 – 2012) between 350 and 550 million Pesos. BIR computation of internal revenue tax collection

35. http://www.blgf.gov.ph/# Base year is 2010, due to the t-3 rule.

36. Capital Gains Tax 3.9, Documentary Stamp Tax 4.9, Donors Tax 0.1 and Estate Tax 0.5 (million Pesos)

37. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/GC.TAX.TOTL.GD.ZS and own calculations

38. See www.international-alert.org/.../Philippines_PolicyBriefShadowEconomie...

39. http://www.international-alert.org/resources/publications/mindanaos-shadow-economies www.international-alert.org/.../Philippines_PolicyBriefShadowEconomie... Steven Schoofs: Out of the Shadows: The Real Economy of the Bangsamoro PPT

40. http://www.bir.gov.ph/images/bir_files/internal_communications_3/Top%20Taxpayers/TOP%20500%20Non%20Individual_arranged%20by%20rank.pdf

41. https://ibonreads.wordpress.com/tag/mining/

42. http://www.philstar.com/business/2014/09/13/1368665/3-more-multi-million-businesses-enter-armm

43. http://www.tripleiconsulting.com/industry-reports/mining-minerals/

44. DILG, The Review Of The 1991 Local Government Code, Presentation To The Coordinating Committee On Decentralization, 23rd January 2015.

45. The IRA would be increasing by about 250 billion Pesos

46. This is also based on 2013 figures obtained from the BLGF, http://www.blgf.gov.ph/#

47. Cities 2013 http://www.blgf.gov.ph/#

48. The lack of cadastral surveys in still about 50% of ARMM, a resulting large informal land market and sketchy titling as well as an above average performance of La Union might be taken as explanation, but can’t explain a 60 times higher collection.